Q3 2023 Evolution of Software Supply Chain Security Report

Phylum specializes in identifying and mitigating software supply chain attacks, focusing on protecting developers against threats originating from open-source ecosystems. By meticulously monitoring and analyzing every package published in real-time across seven diverse ecosystems (i.e., npm, PyPI, RubyGems, Nuget, Crates.io, Golang, and Maven), Phylum provides an unparalleled perspective on potential security threats targeting software packages and the developers that use them. This vigilant approach enables the detection and tracking of attacker behavior across each package registry, rendering crucial and timely insights into the strategies and mindsets of threat actors.

The revelations from the third quarter of 2023 underscore a pressing sense of urgency, highlighting an alarming surge in attack sophistication aimed at developers and package ecosystems. The landscape is riddled with multifaceted threats, ranging from broad typosquatting campaigns on Crates.io and targeted npm attacks, to malware triage inefficiencies in the Python Package Index (PyPI). This escalation in malicious activities and the diversity of the threats encountered emphasize the immediate need for broader security measures and heightened awareness within the developer community to better safeguard our software supply chains against these evolving risks.

Q3 Overview

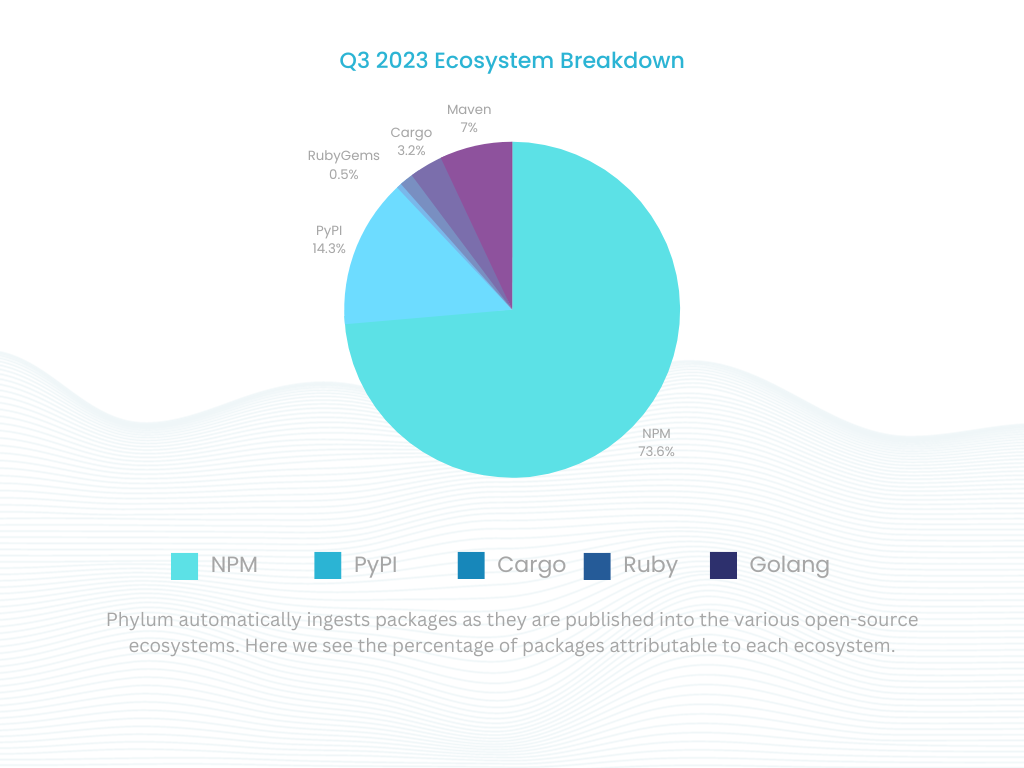

In an alarming escalation of software supply chain threats, numerous packages exhibited harmful or suspicious behaviors congruent with malware-like activity. This quarter, Phylum analyzed 203M files across 3M total packages. This represents a 13.41% increase in files analyzed and a 20% increase in package publications from the previous quarter. The breakdown of packages across each individual ecosystem is captured below.

Across all packages analyzed this quarter, Phylum saw the following behaviors:

- 974 packages targeted specific groups or organizations.

- 10,201 packages referenced known malicious URLs.

- 85,805 packages contained pre-compiled binaries.

- 13,708 packages executed suspicious code during installation.

- 7,894 packages made requests to servers by IP address.

- 5,502 packages attempted to obfuscate underlying code.

- 370 packages enumerated system environment variables.

- 3,662 packages imported dependencies in a non-standard way.

- 1,481 packages surreptitiously downloaded and executed code from a remote source.

- 2,598 typosquat packages were identified.

- 5,033 packages were registered by authors with throwaway email accounts.

- 59,793 spam packages were published across ecosystems.

Across the board, we saw an increase in packages exhibiting behaviors congruent with malware activity compared to Q2 2023. Shockingly, we saw a 47.4% increase in packages targeting specific organizations. These packages often deliver credential-harvesting malware, or exfiltrate source code or other intellectual property. This figure follows the trend we’ve continued to see quarter over quarter: attackers are now beginning to narrow their focus. Instead of running broad typosquat campaigns, they now target specific organizations directly.

One Update Away From Compromise

On January 6, 2023, a user published hardhat-gas-reporter to npm. This package provided legitimate reporting utilities for the eth-gas-reporter project. For nearly 8 months, this package remained dormant with no additional updates. On September 1, 2023, Phylum’s automated platform alerted us to a malicious update that exfiltrated a user's clipboard to a remote server controlled by the attacker. This is not an isolated incident. Whether it’s a malicious author or a compromised account, updates provide a useful mechanism for malware distribution for a patient attacker.

We have established that malware is pervasive across all open-source package registries. However, what is not commonly considered is the fact that even benign packages can serve as a gateway to compromise. Perhaps these packages are more problematic when encountered, as they lure developers into a false sense of security; “I already checked that package,” we tell ourselves.

But the fact remains: installing a package, benign or otherwise, is still executing code written by an unknown individual from the internet on a machine or in a build environment. Doing so brings all the risks one might expect, even if the impacts aren’t realized for many months or years.

Across Q3 of 2023, 208,904 packages received at least one update, which is about 7.5% of all packages published in the quarter. On average, we saw 5.5 updates per package with at least two versions. Updates came sporadically across the quarter, averaging 21 days between each update. Can manual review reasonably keep up with this volume of package updates? Probably not. Though to play devil’s advocate, some organizations won’t deal with all the packages updated during a given timeframe, and will limit their focus to only the ones their developers use. But that approach comes with its own set of challenges, including:

- Package imports into the organization slow software development velocity.

- The skillset required to audit source code manually is expensive.

- Critical security updates will be applied more slowly.

- Human review is error-prone.

That isn’t to say an organization shouldn’t review all the packages used in their development, or limit access to packages in their private repositories. However, organizations should augment this effort with automated triage and governance to better understand the attack landscape more broadly. Benign packages can ship with useful functionality, provide reasonable updates for months or years, then ship out a malicious update sometime later either through the direct actions of the malicious author or via compromise.

Malware authors play on developers’ motivations to ship features by providing utilities to speed up or improve development. Unfortunately, this is at odds with security and results in an organization opening itself up to risks originating from open-source packages. Anyone, quite literally, is one update away from a compromise.

Even the Rust Ecosystem Isn’t Immune to Attacks

On August 16, Phylum identified nine crates intending to typosquat several popular Rust packages. We reached out to the crates.io team after the discovery. The reported crates were immediately yanked, the user account was locked, and the crates were completely removed from the crates.io file store by August 18.

“Our thanks to Phylum for reporting the crates” — The Rust Foundation

The malevolent crates evolved over time, with several early packages containing no malicious component or a copy of PuTTY, seemingly as an experiment to discover what might be possible from a build.rs file. Later versions contained the makings of an exfiltration campaign. Once executed, the packages would attempt to send metadata, including the operating system, IP address and geolocation information of the user’s computer, to a Telegram channel.

As the Rust language grows in popularity, it will more consistently draw the attention of bad actors. At this point, it does not appear that any ecosystem is safe from the distribution of malicious packages. This particular attack illustrates the evolution of this threat landscape. Developers and the organizations that employ them are now prime targets, and the wider software development community has not done enough to stem the tide of malware distribution.

Threats Were More Sophisticated and More Targeted This Quarter

NPM, the Javascript package registry, served approximately 24 billion downloads in a selected week. How many developers verified the integrity of the downloaded code and ensured that it didn’t contain a malicious update or outright malware? The answer is, astonishingly, nearly none of them.

From an attacker’s lens, this is the perfect space to launch an attack: a large, mostly unguarded attack surface and a user base willing to execute unknown code on their machines. This perfect storm means we expect attacks to continue to increase in sophistication and frequency merely because they are so fruitful. The campaigns detailed below should serve as the harbinger of broader attack campaigns to come, and we should prepare ourselves for things like large-scale ransomware attacks, botnet activity, and intellectual property and user data theft originating from open-source packages in the next twelve to eighteen months.

Below, we dig into a few of the more sophisticated attacks in Q3 2023.

Nation State Attacks Targeting Developers

At the end of Q2 2023, Phylum was the first to uncover a series of meticulously orchestrated attacks on npm. These attacks were later attributed to North Korean state-affiliated actors by Github. These attacks continued into Q3, with campaigns against PyPI and additional attacks against npm.

These campaigns were strategically executed and highly targeted, focusing on fintech, financial institutions, and cryptocurrency. These campaigns are a far cry from the malware that dominated these ecosystems in late 2021 and early 2022. Most of the packages published during that timeframe were simple credential stealers, which you might find on Github with a “for educational purposes” disclaimer containing the most rudimentary data exfiltration capabilities.

These new campaigns are different. While we cannot accurately attribute all suspected nation-state activity, the core theme across each is sophistication that demonstrates a technical proficiency by a bad actor that hasn’t been readily seen in open-source attacks. Most alarmingly, the cadence of these attacks is increasing. Underscoring the dire need for active monitoring of software supply chains.

Command and Control via Email Validation

Developers are in a constant time crunch to develop and ship features. Security considerations rarely gain you any story points and generally have a negative draw on development velocity. It is for this reason that utility packages are so enticing. They allow developers to ship features faster because they do not have to write functionality from scratch. Rarely, though, do these packages receive the scrutiny they likely deserve.

On August 24, Phylum’s automated risk detection system identified such an npm package. emails-helper, the package in question, claimed to be an email validation library. A review of the code indicated that it contained a very simplistic but otherwise legitimate email validation tool.

Approximately 6.5 hours after publication, a package update introduced several binaries masquerading as .txt files.

As with most malware in the npm ecosystem, the package executed immediately upon installation. Notable things that stand out about this package, especially compared to early malware publications from several years back, include that it:

- Leveraged DNS as a communication channel.

- Attempted to identify production vs. staging development infrastructure.

- Exfiltrated private SSH keys.

- Implemented an actual encryption scheme for data.

The result was the exfiltration of sensitive data, allowing access to critical organizational infrastructure and distributing a Cobalt Strike Beacon for setting up a persistent command and control (C2) channel.

Fake Software Supply Chain Security

On August 9, 2023, Phylum’s automated risk detection platform flagged a suspicious publication on npm. While investigating this package, we received subsequent alerts on August 10 and again on August 11 about two more packages belonging to this campaign.

As with the previously mentioned campaign, this attack automatically initiated at package installation. Much like the more sophisticated attacks we’ve been witnessing, this campaign leveraged a mixture of encryption, a persistence mechanism, and a C2 system.

Unlike many of the rudimentary attacks by fledgling attackers, the packages involved in this campaign do not include code lifted from some other repository or package. There were no well-known credential stealers, and a review of the code clarified that the package was specifically developed as part of this campaign.

After initiating the install, the package backgrounded a process and periodically beaconed to a benign-sounding/api/captcha endpoint. Any data returned by the endpoint was decrypted and immediately executed.

How does this compare to earlier campaigns? Below we note a few characteristics that seemed to be common amongst early open-source software supply chain attacks.

- Packages were part of large typosquat campaigns and appear opportunistic.

- Packages shipped the final malicious payload with the package itself.

- Aside from periodic basic obfuscation, no real attempts were made to hide the package’s behavior.

- Packages rarely contained any command and control component.

Looking at this particular campaign and most others we encountered during this quarter, we see that almost none of the above holds true. Packages in this campaign:

- Were highly targeted.

- Only 15 packages were released in total.

- The final malicious payloads were not part of the original package and came directly from the attacker after an infection.

- Encrypted data before dispatching it, and only applied light obfuscation to mask the remote hostname, which facilitated its ability to hide in plain sight without drawing attention to actual malicious functionality.

- Contained an actual command and control system that allowed the attacker to issue additional commands, post-infection.

We are trending toward a new normal. An increase in sophistication will make identifying software supply chain attacks more difficult. The targeted nature of these attacks means fewer indicators to hit on, so attackers can easily hide in the noise of millions of monthly package publications. Now is the time to begin fortifying software supply chains.

Source Code Theft

Here’s a look at a timeline from an attack from a few years ago:

- September 2019: Attackers gain access to the organization's network

- October 2019: Attackers test adding code to the project

- Feb 2020: Malicious code is added to the project

- March 2020: The company begins shipping malware-laced updates

Does this ring a bell? It should; it’s the SolarWinds hack that gained tremendous notoriety that year. Access to developer workstations and source code is cause for considerable concern, as it can have devastating impacts on a company or organization.

On July 31, Phylum uncovered a series of package publications that worked to exfiltrate source code and other intellectual property. As many of the malware packages typically identified focus solely on the exfiltration of credentials and authorization tokens, the theft of source code struck us as particularly interesting.

Source code provides information an attacker wouldn’t receive from credentials alone. For starters, one might find hardcoded secrets within the source itself. It also provides an understanding of an organization’s infrastructure and may provide clues to additional points of interest.

More concerning is that an attacker’s access to source code on a developer workstation provides the perfect point to add a malicious modification to an organization's software. All the ingredients are there: remote access, direct access to developers tasked with modifying company code and code execution capabilities.

In this case, we witnessed the attacker testing their campaign over several days by publishing a dozen “developer backup” utilities. This malware crawled through a developer's workstation, looking for configuration files that often contain secrets and credentials, and source code files ending in specific extensions. A zip archive was then created of the contents and uploaded via FTP to a remote server.

While it remains unclear who this campaign targeted, early signs point to financial and cryptocurrency organizations. If we’ve learned anything from the SolarWinds hack, it is that access to source code is the perfect launching point for follow-on software supply chain attacks. If a developer happened to interact with one of these packages, their company could now be distributing malware-laced products to its customers.

Conclusion

The research conducted in the third quarter of 2023 highlights the increasing sophistication of software supply chain threat actors. We are seeing an evolution in techniques and tactics, with many actors migrating away from simple credential harvesters. Late last quarter and into this quarter saw the rise of nation-state activity, with highly technical attackers operating across disparate ecosystems.

Open-source software registries serve as the perfect jumping point for attacks. The attack surface is large and mostly unguarded. Success in this domain often means direct access to developer workstations or production infrastructure, and the effort required to be successful is astonishingly low.

While progress is being made, the open-source ecosystem remains riddled with risks, and the escalating sophistication of malware continues to pose a persistent threat to developers. As we collectively get better at identifying and removing malware, it forces the malware authors to produce more subtle and technically complex malware. 2023 will serve as the start of the great cat-and-mouse game in software supply chain security. We expect the volume of trivial and relatively rudimentary malware packages to remain steady. However, underneath this slight disturbance exists the real problem: increasingly sophisticated, highly targeted attack campaigns originating from open-source packages.

Have you already been impacted? How would you know?

Phylum Q3 Research Recap

We routinely publish research on campaigns and targeted software supply chain attacks. While these do not cover all of the campaigns we see, they highlight some of the more interesting attacks and behaviors from this quarter.

- Sensitive Data Exfiltration Campaign Targets npm and PyPI

- Large Typosquat Campaign Targeting React and Angular

- Nascent Malware Campaign Targets npm, PyPI, and RubyGems Developers

- Dormant npm Package Update Targets Ethereum Private Keys

- Cryptocurrency Miner Masquerading as GCC Compiler Found in NPM Package

- NPM Package Masquerading as Email Validator Contains C2 and Sophisticated Data Exfiltration

- Rust Malware Staged on Crates.io

- Sophisticated, Highly-Targeted Attacks Continue to Plague npm

- Typosquat of popular Ethereum package on npm sends private keys to remote server

- Targeted npm Malware Attempts to Steal Company Source Code and Secrets

- June’s Sophisticated npm Attack Attributed to North Korea

About Phylum

Phylum defends applications at the perimeter of the open-source ecosystem and the tools used to build software. Its automated analysis engine scans third-party code as soon as it’s published into the open-source ecosystem to vet software packages, identify risks, inform users, and block attacks. Phylum’s open-source software supply chain risk database is the most comprehensive and scalable offering available. Depending on an organization’s infrastructure and appsec program maturity, Phylum can be deployed throughout the development lifecycle, including in front of artifact repositories, in CI/CD pipelines, or integrated directly with package managers. Phylum also offers a threat feed of real-time software supply chain attacks. The company is built by a team of career security researchers and developers with decades of experience in the U.S. Intelligence Community and commercial sectors. Phylum won the Black Hat 2022 Innovation Spotlight Competition, was named to Inc. Magazine’s 2023 Best Workplaces, and became a Top Infosec Innovator by Cyber Defense Magazine. Learn more at https://phylum.io, subscribe to the Phylum Research Blog, and follow us on LinkedIn, X and YouTube.